Cyber security takes center stage with new presidential directive

Over the last decade, the topic of cyber security has been treated more as a partisan political football in the United States Congress rather than a national security concern. But this week, the course of that discussion took a radical change in direction.

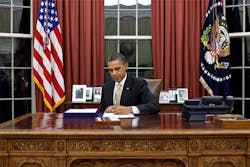

Prior to Tuesday’s State of the Union address, President Obama signed an executive order making the protection of America’s information and data assets a priority. Coupled with the Presidential Policy Directive on Critical Infrastructure Security and Resilience released by the White House earlier in the day, it was clear that it was not "business as usual" when it came to defining the threat.

The Cyber Security Act failed in its last two attempts at passage in Congress, and while the Obama administration has said all the right things when it came to providing safeguards for the nation’s information assets, action was in short supply. Never before has the president spent as much time discussing cyber security in a public forum as he did Tuesday; in fact, he didn’t mention it at all in his 2010 and 2011 addresses.

But in Tuesday’s speech, the president made it clear that cyber security must be front-of-mind, and that a spirit of cooperation between government and industry would hold the key to creating a viable strategic plan. “America must face the rapidly growing threat from cyber attacks,” Obama said. “We know hackers steal people’s identities and infiltrate private e-mail. We know foreign countries and companies swipe our corporate secrets. Now our enemies are also seeking the ability to sabotage our power grid, our financial institutions and our air traffic control systems. We cannot look back years from now and wonder why we did nothing in the face of real threats to our security and our economy.”

The Executive Order (EO) gives government agencies a year to devise a “baseline framework” for cyber security that will incorporate peer-based standards and industry best practices that are already in place in other critical infrastructure sectors like utilities and gas and oil pipelines. The creation of a critical infrastructure council, run by the Department of Homeland Security, will include members of the Department of Defense, Commerce and Justice, along with the National Intelligence Office. The goal is to prevent malicious penetration of computer systems in key industries and infrastructure by hackers, criminals and enemy states.

“I think the president threw out a challenge in his address by specifically noting this was a bipartisan issue — he was provocative by noting that,” says Lisa J. Sotto, managing partner of the New York office of Hunton & Williams LLP, where she heads the firm’s Privacy and Data Security practice. She also serves as Chair of the DHS Data Privacy and Integrity Advisory Committee, “He is challenging our legislators to get together on this and move forward,”

While Sotto admitted that much of what was presented by the president was a “regurgitation of what has been seen before,” she is still encouraged.

Perhaps the most dramatic tenant of the EO is the urgency the administration has put on information sharing among public and private partners. Within the next 120 days DHS will be working closely with the U.S. attorney general, the secretary of Homeland Security and the director of National Intelligence to create a roadmap that will help with the timely production and release of unclassified cyber threat reports, including those aimed at specific industrial sectors. The EO addresses the need to protect intelligence and related law enforcement sources, methods, operations and investigations. At the same time, it instructs the DHS and DoD to create procedures that broaden the effectiveness of the Enhanced Cyber Security Services program for all the nation’s infrastructure.

Howard A. Schmidt, the former White House cyber security coordinator, told the Washington Times that there have been lengthy negotiations about the roles and responsibilities of government agencies – especially DHS – moving forward. He said that the new EO defines “specific responsibilities” for Homeland Security to secure federal computer networks.

Information sharing between the private sector and the federal government is not new. There are open lines of communication between the Feds and 17 key industrial sectors; however, Schmidt admitted that the DHS-private sector relationship needed to be stronger.

For experts like Sotto, she sees the new information sharing landscape coming with more responsibilities related to the private sector. “The key issue is information sharing,” she says. “I view it as both a blessing and a curse — it is blessing in that there will be much faster delivery to the private sector on cyber threats and better coordination between the government and private sector. The curse is that now the private sector will have knowledge of threats, and they will have to act on them.

“I think the private sector and government are running scared,” she adds. “Everybody is gravely concerned and this president is the first one to raise this to a different level – appropriately so given the threats we’ve experienced over the past several years. The fact that he spent a good amount of time on this topic in his speech shows a great level of concern.”

Another partner in the new cyber security strategy is The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), which has been charged with establishing the peer-based, voluntary security framework that will serve as a pseudo book of standards for critical infrastructure based on input it receives from federal, state and local governments, standards-setting organizations, industrial advisory groups and infrastructure owners and operators.

Evan Wolff, who serves as director of Hunton & Williams’ homeland security practice, says there is a precedent for how the White House and its agency partners are rolling out their plan. “I think the cyber security framework will have some intended and unintended uses,” he says.

Wolff continues to say that the new set of policies will aid insurance companies when it comes to litigation settlements because they will now have a defined set of rules to play by. The new rules will also have a role in an organization’s internal audit.

DHS will be working to compile a list of critical infrastructure assets and their greatest risks that will serve as a checklist of best practices. Wolff, who once served as an infrastructure protection advisor to DHS senior leadership, says the EO creates a mechanism by which private owner/operators could be forced to adopt those best practices. When a company gets notified by DHS as a result of a perceived vulnerability or breach, there will be a standard set of procedures to become “compliant” and rectify the issue.

“They will understand the basis for that decision and there will be a process where they can actually decide if they want to get off that {voluntary} list or redress the process. DHS has done this before when addressing regulatory issues in the chemical industry (the CFATS program) and coming up with risk management assessment processes and lists,” Wolff says.“If a company is notified by DHS of some sort of cyber threat to their organization or they discover it on their own they will not be allowed to ignore it. Government contractors will be advised to adhere to the peer-based standards at risk of losing their ability to do business with the government.”

Sotto agrees that the financial element is a key to putting teeth to the voluntary standards framework. “This is critical point. If anything is persuasive in this entire scenario, it is the power of the purse. That possible sanctions will impact the ability to get a government contract, it is highly incentivizing.”

From the perspective of a security practitioner like Martin Zinaich, information security officer for the city of Tampa’s Technology and Innovation Department, excitement is tempered by the reality of the mandate. “I see the announcement as a small step forward, but not one giant leap for mankind,” he says. “We already have numerous frameworks in the information security space (ISO27002, NIST, PCIDSS) that do a good job defining what ‘should be done’ — but the work is getting businesses to adopt and take that risk seriously.

Zinaich, who is a member of Wisegate — a network of IT experts and an information service for senior IT professionals — adds that most only react after a major issue. ”Until then they have a very high risk tolerance with technology,” he says. “I do think it is positive to see this issue raised at the level of the President.

“Businesses simply do not get the business risk paradigm shift from mainframes, with their centralized and isolated security, to a distributed PC environment connected on an Internet that was never designed to be secure,” Zinaich concludes. “Add to that mix the anytime/anywhere business-induced requirements and you have even more exposure.”