Research shows how schools adopt access control

New research from the National Association of School Resource Officers (NASRO), the National Association of School Safety and Law Enforcement Officers (NASSLEO) and security technology firm Wren Solutions paints a picture of access control technology adoption at our nation's schools.

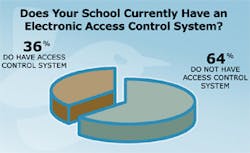

According the research, electronic access control systems are not used by most schools. Sixty-four percent of the survey's respondents said they were not using electronic access anywhere in their facilities. Ones that did use access control devices predominantly use them at main school entrances.

According to Andy Wren, president of Wren Solutions, a video surveillance technology firm which helped organize the research, the results paint a picture of slow adoption of access control technologies. And he says that doesn't surprise him in the least.

"Their job is to educate," said Wren. "Security is not always top of mind. Security has moved up the ladder in mindshare, but a lot of these schools still struggle to understand the need. There is access control in every building, obviously, because every [exterior] door has a lock on it, but a vast minority really have widespread deployments [of electronic access control]."

Budgets always a problem

According to Dr. Richard Caster, the executive director of the 8,000-member National Association of School Resource Officers (NASRO), many school safety professionals are very aware of security technologies, but there's not always money to buy these systems.

His sentiments were reflected in the Wren/NASRO/NASSLEO research, which found that of the 64 percent of schools not currently using electronic access control, almost three-fourths of those said that was due to funding. And if they were to spend money on upgrading school access control, just half said they would be using their existing school budget. Most (69 percent) said they would have to turn to grant money from the federal or state level.

"Money is an issue," said Caster. "Most schools would like better control over the building and at entrances, but it will always be a money issue. It's a matter of affordability. I keep telling them [security technology companies] that schools need good information and good advice on what they can do and what they can really afford."

Even though cost is often seen as a driving factor, Caster says that schools can sometimes find a return on investment by adoption electronic access control

"What we've found is that in the long run, it ends up saving you money," said Caster. "The problem with keys it that they get lost. Once a key is lost, it becomes a security problem. And then you have to change locks or tumblers. And there are problems with regular failure and vandalism, like a student putting glue in the lock."

Peter Pochowski, executive director of the 1,500-member National Association for School Safety and Law Enforcement Officers (NASSLEO), said that with budgets for security very tight, most schools have remained in a reactive stance.

"The best crisis plans are written the day after a crisis," noted Pochowski. "You have to wait until a crisis for that to happen. [Similarly,] schools tend to spend on security after a crisis."

Despite those problems, Pochowski said the money can be found if a school really needs it.

"Grant money is getting tight, but there is some grant money out there," said Pochowski. "You have to be creative in how you fund these."

Pochowski said that besides federal grant monies, some schools have done fundraisers and others have turned to non-profit foundations to help them boost their security. He also cautions schools to consider technology implementations on a case-by-case, local basis.

"There are people who use scare tactics in the education market to sell their security products," said Pochowski. "You are much more likely to be killed by lightning than to be killed in a school. People have to examine what is reasonable and what their school can afford."

Caster added that he doesn't think that security funding for schools will change for the better anytime soon.

"I'm not very optimistic that there's going to be very much money to put this technology into schools," said Caster.

Lockdown technologies

One thing also learned in the research is that three-fourth of respondents were not sure they could lock down their school in the case of an emergency. And only 28 percent of respondents were confident that their exterior doors would securely lock in the case of an emergency lockdown.

Admittedly a lockdown, noted NASRO's Richard Caster, can take many forms. A lockdown in one situation could mean closing and securing exterior doors. In another place, it could be more of a "shelter in place" situation where classrooms or wings of a facility need to be locked down because the threat is inside the building.

The problem, of course, is that there are so many doors to be concerned with in a school environment – especially at high schools.

"A high school with 2,000 kids has a lot of doors," said Caster. "The thing with most schools is that lockable interior doors is an issue right now. Many schools don't have lockable interior doors.

But Caster said also that lockdowns mean much more than deadbolts and magnetic locks. He says that preparing for lockdowns also means training staff on new policies.

"When we encourage schools to do lockdown drills, we tell the teachers who lock a classroom or area of the school that 'You don't open that door for anybody, even if you recognize that voice,' When the situation is done, it is the administrator who should then unlock the doors from the outside."

Still, the research does indicate that schools generally recognize the value of lock-down technologies like an electronic access control system. Ninety-one percent of the respondents said it was critical to be able to lock down the school if an emergency were to happen; they just aren't able to do so yet.

Commenting about the research, both Caster and Wren Solutions' President Andy Wren agreed that before adopting any new security technology, schools really have to examine their risk profile. And both agreed that one thing is changing for the better: The school resource officer or school police officer is becoming more and more of a risk and security consultant. Besides being recognized as member of law enforcement in the school halls and cafeterias, Wren and Caster said the SRO should be sitting as part of the emergency planning meetings and conducting assessments of the school.

"We are seeing the role of the SRO change," said Caster. "Any school that is fortunate to have an SRO has a ready resource of information that most administrators don't have. They need to be at the table for crisis management -- we're talking natural disasters as well as manmade. That person will bring the expertise of what they learned in the academy. Most of our officers in schools will have also served some time on the streets. They are becoming an integral part of security planning. You're wasting a resource if you don't involve him or her."

Andy Wren said that besides the changing role of the SRO, schools are being forced to consider access control as they examine their risk profile. In the research, they found that 93 percent of schools that use electronic access control were using it at the front doors and main entrances. Very few were using identity-based electronic access control inside the school, and electronic access was rarely used to secure science chemical storage areas. This he says, indicates that schools and the public "may not fully understand their risks."

The research was the third part in a four-part series of research that Wren is doing on school security. Previous research examined security at schools in Texas and the Midwest.