I want to cover the implications I see emerging from the recent Security and Exchange Commission’s rules on cybersecurity disclosure. Before we delve into the latest federal edicts, I felt it instructive to take you back a couple of generations to a time before the information age when the Feds decided to weigh in on safety.

In the waning days of December 1970, President Nixon signed the Occupational Safety and Health Act, also known as OSHA. The new regulations were deemed necessary by Congress in the wake of the industrial boom that allowed the United States to build the tanks, aircraft, and ammunition necessary to win World War II. As post-war production shifted to satisfying the demands of a war-weary population, manufacturers started cranking out automobiles, appliances, and housing materials for the Greatest Generation.

During the war years, the American people (and hence Congress) tacitly avoided discussing the soaring rate of industrial accidents as the urgent demand for war material was considered a much higher priority than the oversight of workers’ safety and health concerns. The rate of industrial accidents soared, but we kept the national focus on defeating tenacious enemies in two major theaters of war.

Congressional Oversight

After victory was declared and we returned to peacetime production, industrial accidents remained high. Over the next two decades, Congress felt pressure to intervene on behalf of both union and nonunion workers who had little to no recourse when they were injured, maimed, or killed on the job. In addition, this period also introduced the chemical revolution as new chemicals and compounds were being developed for use in everything from clothing to fertilizer. The burgeoning environmental protection movement would lend its imperative to the creation and passage of the OSHA legislation.

I recall this period well - yes, I am that old. At the time, my World War II combat veteran father was working in the career he began when he returned from his duties as a naval aviation metalsmith in the Pacific Theater. He had worked with the Big Employer in our company town - John Deere - as an experimental machinist. As such, he worked in a factory that designed and built plows and planters for farming applications. OSHA would have a major impact on both my father as a union factory worker and his employer.

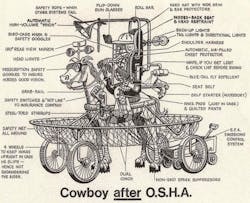

I remember with distinct clarity the day in December 1970, when my father arrived home at his usual time and dropped a paper leaflet on the kitchen counter next to his Thermos metal lunch bucket, I was a cartoon that had been passed around the factory ridiculing the legislation. Now, mind you, this was decades before computer-generated graphics and email. Some clever people with artistic skills got out their pens and scratched out the cartoon on a piece of paper. Then, it had to be mimeographed onto other sheets of paper - likely at a printing press operation. The resultant flyers were then distributed by hand from worker to worker. Amazingly, I found that cartoon still available in its digital reincarnation on the internet just today.

Here it is:

I remember being fascinated by it. I wasn’t sure if the cartoon was meant to convince the workers they didn’t need the strict OSHA requirements or was just meant as a satirical perception of the new legislation. My dad was not one for labor activism, so I concluded he just brought it home to show my mother. It became just another signpost in his union machinist’s work life.

Government Regulations, Why Not

Now let us return to the present and my career as a cybersecurity professional. We have a new federal reporting requirement courtesy of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission to ostensibly provide transparency to regulated businesses regarding their risk management priorities and response to breaches and attacks on their information resources. As I investigate the new rule, I am reminded of something I said from the podium at a conference two decades earlier: relying on government regulations in cybersecurity is like driving a high-performance sports car using only the rear-view mirror.

Like the OSHA legislation, the seeds for its germination began decades earlier. The need for federal oversight of worker safety had been identified at the start of the Industrial Revolution and was only drawn to the fore by the challenges of post-World War II-era production. It was ultimately signed into law in late 1970.

So, it is with this SEC ruling. The requirements for organizational transparency were identified long before the term ‘cybersecurity’ was even coined. As organizations collected and stored personal information on citizens, customers, and users, it became readily apparent that individuals needed to have a say in how that information was used, stored, and protected. This latest ruling is just another step in that direction and a few decades later.

As with driving that sports car with only the rear-view mirror, demanding adherence to rules and policies that have their roots in the past, there are significant emerging vulnerabilities not considered by the policy writers. A tight timeline for reporting breaches sounds like a good policy until you consider that even providing an exact definition of a breach is difficult at best. Additionally, the tight timeline may require an organization to make a public statement that aids the attacker to further exploit the organization as the response team has yet to fully remediate the exploited vulnerabilities.

Risk-Based Guidelines

The risk management aspects of the legislation are also problematic. Most large, private businesses have already embraced cybersecurity as a key component of their corporate risk management strategy. Now, the SEC would like you to outline it publicly for transparency. However, this could actually add new risks to your corporate governance as you are publishing sensitive internal analyses and data.

This new regulation is not dissimilar to the Computer Security Act of 1987: another federal attempt to define a common risk-based approach to managing information security and governance. I was a member of a team of government personnel who were tasked with reviewing the submissions from all the federal departments and agencies affected by the new law. We clawed through each security plan and wrote up responses to every submitted computer security plan. Here, thirty-six years later, we are asking all our private organizations to do the same with the addition of near-real-time incident reporting.

There is nothing new here except for additional paperwork and tick box security compliance. The beleaguered CISO and their staff will have another government mandate that requires compliance. The investors, and the public in general, will not have much more faith in an organization’s ability to manage its critical data and digital infrastructure assets. Perhaps we need a new cartoon with a CISO driving their sports car in reverse amid a tornado of government compliance forms and spreadsheets.

John McCumber is a seasoned cybersecurity executive with over 25 years of progressive experience in information assurance and cybersecurity operations, acquisition, management, and product development. Expertise in corporate security policy development and implementation of security in information technology design. Recent experience working with Congress on cybersecurity legislation and professional advocacy. He is a long-time columnist with Security Technology Executive magazine and a contributing writer at Ordinary Times. John is a retired US Air Force officer and former Cryptologic Fellow of the National Security Agency. During his military career, John also served in the Defense Information Systems Agency and on the Joint Staff as an Information Warfare Officer during the Persian Gulf War.

About the Author

John McCumber

John McCumber is a security and risk professional, and author of “Assessing and Managing Security Risk in IT Systems: A Structured Methodology,” from Auerbach Publications. If you have a comment or question for him, e-mail [email protected].