Do you routinely dig into your incidents to identify the root causes and pass on the learning to those who need to know? If not, plan on logging more of the same and documenting allegedly smart people repeating their mistakes — or worse.

Root cause analysis (RCA) is an established process in quality management, engineering and risk management. It may take other forms in our business such as lessons learned, incident post mortems and after action reviews (AAR), but the objectives are the same: to objectively, relentlessly identify the factors that created a failure of a control or set of controls so that those conditions may be prevented in the future. This is about nailing the real cause, not the lightly assumed symptom. Communication is the critical step to record the process and close the accountability loop.

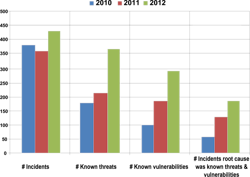

In this example, we see a corporate security organization that has formalized a process (or combination of analytical processes) focusing on continuous improvement in security risk management. Their approach seeks to understand the degree to which known threats and vulnerabilities are a factor in this company’s security incident experience. The idea is that where we can confirm that the threat is known and the vulnerability that was exploited, we have the essential elements to avoid or prevent this incident. But it is the notion that so many of the defects in protection that are implied here are repetitive that drives the relevance of this summary analysis. Moreover, from a perspective of consequential risk, these may be events that contribute to personal injury, litigation for defective security, embarrassment to brand and likely Board inquiries.

RCA is focused on identifying what factors verifiably contributed to the magnitude, timing and location of a risk incident. It forces a broad consideration of multiple sources of incident causation. A variety of human, physical, technical or other factors may contribute to the exploitability of asset vulnerability. What are they? If accidental, what conditions led to the breach? If man-made, how does it appear they were discovered and exploited by the adversary?

Success in this process is changed behavior, tested elimination of process defects, increased awareness of individual accountability and eventual reduction or elimination in recurrence of like events. Where there may be multiple causes, an advantage of RCA is in the identification of a single solution that closes down more than one exposure or isolates a simple, low-cost approach.

Unfortunately (or fortunately as the case may be), the learning frequently focuses on the adequacy of some element of the security program. The absence of awareness often lies in the lack of an established or properly directed program. The failure to address leading indicators like nuisance alarms, inadequately trained personnel, poor planning or execution in incident response, lack of maintenance of critical security components or program elements; are all found in well-executed AARs and RCAs.

Leverage the learning — I have often heard a colleague say “what we need around here every once in a while is a well-managed incident that grabs management’s attention.” The emphasis is obviously on the “well managed” but the notion is sound. Risk is inevitable and the degree to which we are prepared typically tells the tale of the degree of consequence. Engaging a team from the affected business unit, Security and others in corporate governance speaks more to avoiding future risk than taking prisoners. Success can be celebrated and best practices identified or we can learn together what could have been done better.

Companies that fail to learn from their mistakes are destined to repeat them. Be a leader and set the stage for learning.

George Campbell is emeritus faculty of the Security Executive Council (SEC) and former CSO of Fidelity Investments. His book, Measures and Metrics in Corporate Security, may be purchased at www.securityexecutivecouncil.com. The SEC draws on the knowledge of security practitioners, experts and strategic partners to help other security leaders initiate, enhance or innovate security programs and build leadership skills.