School Security Programs are Rolling Out Digital Mapping

When first responders arrive at the scene of a critical incident such as a mass shooting, one of the most crucial tools for an effective response is the availability of accurate, detailed floor maps of the buildings where the offenders and victims might be located.

But often, that isn’t the case. While many school districts have adopted a multi-layered security approach to protect students and staff from gun-related violence, the average age of educational school buildings in the U.S. is 49. Statistics show that an estimated one-third of public schools have at least one portable building on campus.

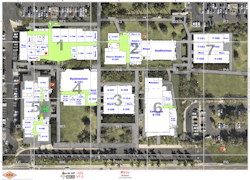

As a result, many districts don’t have updated, accurate maps of their facilities, which can potentially frustrate public safety efforts to locate suspects and victims and increase response times.

This scenario has played out in real life: the U.S. Department of Justice’s 600-page critical incident review of the Robb Elementary School mass shooting in Uvalde Texas, noted that as law enforcement prepared to confront the gunman, the map they were reviewing was missing important details, including windows that were present and a door that connected between two classrooms.

With the increase in attacks at schools and the number of fatalities per episode also going up recently, more than 20 states have enacted or proposed digital school mapping measures in the past few years, according to an Associated Press analysis aided by the bill-tracking software Plural. Florida approved $14 million in 2023 for such programs, Michigan has allotted $12.5 million, and New Jersey has allotted $12.3 million, the AP reported.

Several firms, such as Critical Response Group, Centegix, GeoComm and Navigate 360, have been offering digital mapping services to school districts and other facilities as officer and institutional response to these incidents continues to see more public scrutiny.

CRG CEO Mike Rodgers says that in the 14,000 schools the company has mapped since the beginning, he hasn’t found a single floorplan map that was 100% accurate—even in nearly brand-new schools.

The company, which was founded in 2016 and has 175 employees, focuses primarily on schools, although CRG has been hired to do maps for major sporting events and facilities.

But Rodgers says the bigger part of the company’s offering is the implementation work to ensure maps on file are accessible and understood by public safety. When a school is brought into their system, CRG works with law enforcement to integrate it into their system and how it’s used.

CRG typically starts at the emergency response center to ask what technology is used and how maps are integrated. Then, employees work with responding fire and police departments, sheriff’s departments, and state patrol agencies to implement the system and train.

CRG also re-walks every structure annually to verify maps are accurate, and customers can submit changes spontaneously to be entered into the maps on file.

Rodgers says there are 15 states – including large ones such as Florida, Illinois, Texas and Michigan -- that have passed legislation to make school mapping a mandatory part of their security program, including ensuring the maps are up to date and on file with public safety and will function with their technology.

Rodgers believes there will be major expansion of this technology in other states as they look to adopt best practices from neighboring states.

“We never started this company to make any money. We only started it to solve a very specific problem. So early on we realized the need to go to every structure and verify its accuracy. And if it changes six months in, we’ve got to go back and re-walk it to ensure data that could be used to save a life is correct.”

Small Idea Grows

Rodgers’ family has a 130-year history in public safety, with his father being a fifth-generation police officer. Rodgers graduated from West Point in 2008 and deployed in Afghanistan more than half a dozen times, often working on special operations raids during the nighttime.

Rodgers says he was introduced to a specific mapping technique mandated in the military that eventually paved the way for the company to start. During a short stint teaching ROTC at Princeton University, Rodgers says he became worried about what he believed to be a low level of preparation and planning for a crisis, should one occur, at his wife’s elementary school where she taught.

He used a mapping technique he’d learned overseas and applied it to her Ocean County, N.J school. “Along that process, I had no intention of starting a business. I only wanted to solve this problem at my wife’s school,” Rodgers says.

After working to get the issues at his wife’s school addressed, Rodgers expanded his work with school districts in Ocean County and then throughout the state.

‘Lack of Understanding’

Rodgers believes one major reason many schools don’t have updated maps is “a lack of understanding of the problem” and assuming because there are floorplans police departments will know how to navigate their schools or already have the blueprints on file.

“A lot of times, we will see a school district will e-mail the floor plans to a police department, but the plans are wrong, and they’re not compatible with the software that police departments are using,” he says. “The other piece is just a lack of technical ability to execute the maps in a file format that's compatible with police departments.”

Rodges cites an FBI study that says 80% of communication during an emergency is about location, “and the reason is they're communicating about a structure that they've never been into before and no one's familiar with it,” he says. Not having an accurate map slows down the ability of first responders to communicate and navigate efficiently and may slow down response times.

“Imagine when you show up to a building you've never been to before and you're told to be in the art room as quickly as possible, but you've never stepped into this building before. How do you even know what door to run through?” he says. “That’s where we really see this technique and technology applying well, by just simplifying indoor navigation during an emergency response.”

An example Rodgers shared was The Covenant School shooting in Tennessee when first responders arrived outside the door and a teacher ran out and said they needed to go to the Enchanted Hallway inside. “And you hear the officer saying, ‘Where is that?’ And that's not his fault. She's worked there for 10 years, and he's never been there before,” he says.

“There’s an inability to communicate about a specific location, but the communication and navigation doesn’t just stop there. Once the officers get in there and neutralize the threat, how do they communicate to the additional responding officers, the medical technicians, or the firefighters that are now also showing up to this location they've never been to before?”

In addition to inaccurate maps, software incompatibility is another challenge. Public safety professionals want a “common operating picture,” but those responding may all have different software systems. Rodgers says the company has developed its technology so the maps it provides work with any system.

CRG accomplished this, he says, using a combination of different software packages -- in-house, off the shelf and from the military -- to create their maps. Rodgers believes the first-responder backgrounds of his employees is important to implement an effective business.

“It’s also how we put the maps into the systems. When they go to a school or a building, every other mapping company says, ‘Okay, buy my map and look at it through my mobile application.’ The unfortunate reality is the police department is never going to look at that map in that mobile application,” Rodgers says. “They’ve already got three different software platforms they use daily. If you're interested in solving the problem, you must put the maps into an already-deployed tool.”

About the Author

John Dobberstein

Managing Editor/SecurityInfoWatch.com

John Dobberstein is managing editor of SecurityInfoWatch.com and oversees all content creation for the website. Dobberstein continues a 34-year decorated journalism career that has included stops at a variety of newspapers and B2B magazines. He most recently served as senior editor for the Endeavor Business Media magazine Utility Products.